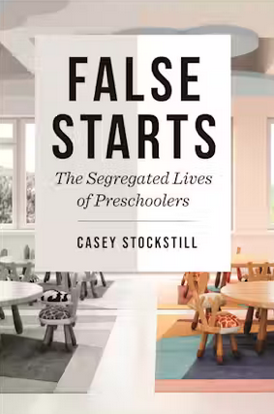

False Starts

Breve Descripción

En las últimas dos décadas, cuarenta y cuatro estados han ampliado el acceso a la educación preescolar, a menudo citando la educación preescolar como una política contra la pobreza. Sin embargo, como muestra Casey Stockstill, dos tercios de los centros preescolares estadounidenses están segregados, concentrando principalmente a niños pobres de color o a niños blancos adinerados en escuelas separadas. Stockstill sostiene que, como resultado, los centros preescolares segregados afianzan la desigualdad en lugar de alterarla.

Breve descrição

Nas últimas duas décadas, quarenta e quatro estados expandiram o acesso à educação pré-escolar, citando frequentemente a educação pré-escolar como uma política anti-pobreza. No entanto, como mostra Casey Stockstill, dois terços das pré-escolas americanas são segregadas, concentrando maioritariamente crianças de cor pobres ou crianças brancas ricas em escolas separadas. Stockstill argumenta que, como resultado, as pré-escolas segregadas consolidam a desigualdade em vez de a alterarem.

Full description

An inside look at the racial and class divides between Head Start and private pre-K classrooms for children and their families

The benefits of preschool have been part of our national conversation since the 1960s, when Head Start, a publicly funded preschool program for low-income children, began. In the past two decades, forty-four states have expanded access to preschool, often citing preschool as an anti-poverty policy. Yet, as Casey Stockstill shows, two-thirds of American preschools are segregated—concentrating primarily poor children of color or affluent white children in separate schools. Stockstill argues that, as a result, segregated preschools entrench rather than disrupt inequality.

Stockstill spent two years observing children and teachers at two preschools in Madison, Wisconsin. Madison, like many other small and medium cities in the United States, is segregated, with affluent and middle-class white people and working class or low-income people of color occupying different sectors of the city. Stockstill observed one preschool that was 95% white and another that was 95% children of color. She shows that this segregation was more than a background variable or inconvenient image; segregation had an impact on children’s experiences in multiple ways, but especially in the ways they spent their time, the supervision and instruction they received, and the ways they learned and socialized with other children. Stockstill shows that even in high-quality preschools that on paper have similar resources, de facto segregation creates different school experiences for children that ultimately reinforce racial and class inequality.

False Starts suggests that as we continue to invest in preschool as an anti-poverty policy, we need a fuller understanding of how segregated classroom environments impact children's educational outcomes and their ability to thrive.

Pedagogy & Education

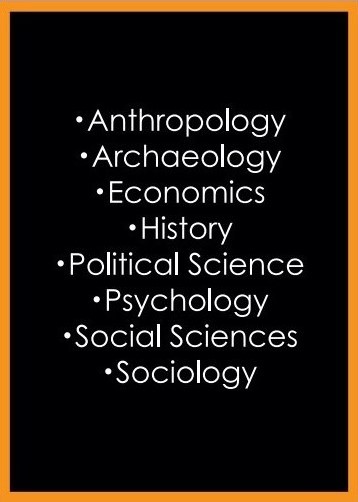

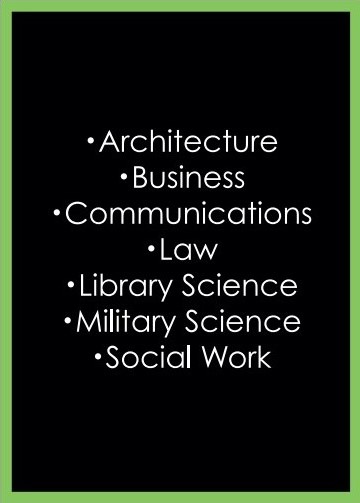

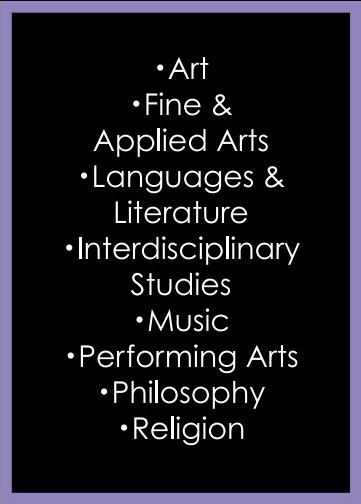

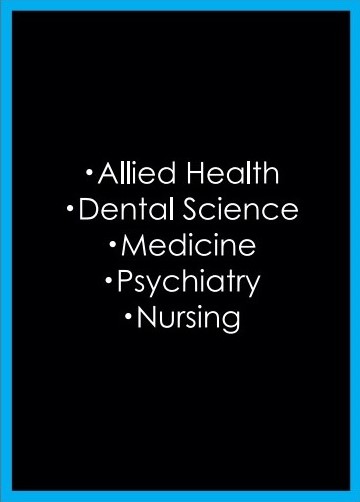

otras áreas de / interés...

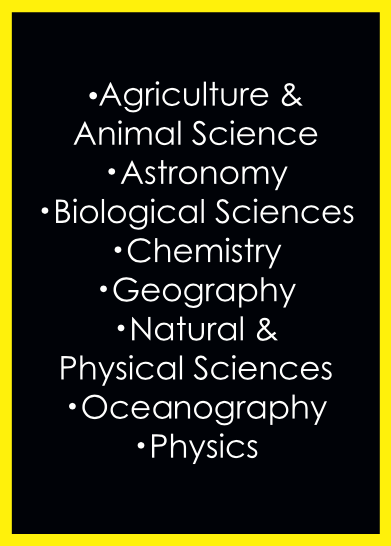

other areas of / interest...

outras áreas de interesse...

¿Buscas un título en un área específica?

Looking for books in a specific area?

¿Procurando livros em uma área específica?